Life, eternal

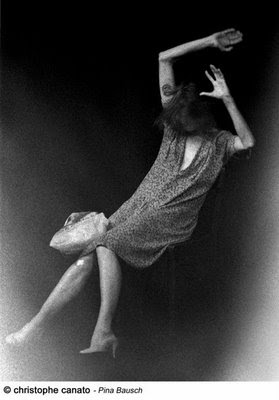

Christophe Canato’s series Ad Vitam Aeternam (To the eternal life) records a time capsule: a small village in the north of France that appears to have been struck by a fairy tale curse that has sent the entire population to sleep. Perhaps sleep isn’t quite the right word—it suggests something at rest soon to awaken, dreaming, kicking, active on a mechanical level. The state of Canato’s village is more akin to suspended animation. The rust doesn’t spread, the buildings’decay is arrested, the abundant weeds grow no worse. Blowflies have ceased to buzz in windowsills. Layers of peeling wallpaper hang precariously, fluttering flipbooks of bygone styles. Decades of pickled vegetables remain in cellars, already embalmed. Even the dust motes are immobile, forming solid walls mid-air. The village has run out of time,

literally, and Canato reveals it as a new Pompeii.

At the centre of the village is an ancient building: a church which has survived five hundred years of natural and human disasters. At different points in its history it has been contained within the borders of this nation or that region, threatened by men with footfalls governed by drumbeats, threatened by men on horseback, men in tanks. The village is much more ancient, resting on thousand years of stratified human waste. Every time the village has been levelled, its people have simply rebuilt. Yet, improbably, the church has remained standing, oblivious of the insect lives of the creatures that have worshipped within its walls.

I imagine the village gradually changing pace, slowing down. The old people start dying, leaving mouldy attics full of dead doves, arcane farming equipment, a bride’s trousseau kept aside for a daughter who never came home. The young people leave for city jobs and only visit for funerals. The church bells ring irregularly, barely noticed—the villagers no longer rely on the schedule of prayer to tell the time of day.

Coming from a much more frenetically paced world, Canato stumbles upon the slumbering village like a lost traveller. An unnerving quiet pervades the site. It seems like an unknown atrocity has emptied the place, some nuclear disaster like Chernobyl or Fukushima, but nothing so catastrophic has caused people to abandon these buildings. The anachronistic contents of the houses, neatly packed away, show the village simply as a casualty of the slow demise of a centuries-old way of life, still visible as ruins, and at its centre an ancient church. This place waits, undisturbed, as if for the fabled kiss that can bring life back to cold, dead lips.

Thea Costantino, Curtin University, 2013

Christophe Canato’s series Ad Vitam Aeternam (To the eternal life) records a time capsule: a small village in the north of France that appears to have been struck by a fairy tale curse that has sent the entire population to sleep. Perhaps sleep isn’t quite the right word—it suggests something at rest soon to awaken, dreaming, kicking, active on a mechanical level. The state of Canato’s village is more akin to suspended animation. The rust doesn’t spread, the buildings’decay is arrested, the abundant weeds grow no worse. Blowflies have ceased to buzz in windowsills. Layers of peeling wallpaper hang precariously, fluttering flipbooks of bygone styles. Decades of pickled vegetables remain in cellars, already embalmed. Even the dust motes are immobile, forming solid walls mid-air. The village has run out of time,

literally, and Canato reveals it as a new Pompeii.

At the centre of the village is an ancient building: a church which has survived five hundred years of natural and human disasters. At different points in its history it has been contained within the borders of this nation or that region, threatened by men with footfalls governed by drumbeats, threatened by men on horseback, men in tanks. The village is much more ancient, resting on thousand years of stratified human waste. Every time the village has been levelled, its people have simply rebuilt. Yet, improbably, the church has remained standing, oblivious of the insect lives of the creatures that have worshipped within its walls.

I imagine the village gradually changing pace, slowing down. The old people start dying, leaving mouldy attics full of dead doves, arcane farming equipment, a bride’s trousseau kept aside for a daughter who never came home. The young people leave for city jobs and only visit for funerals. The church bells ring irregularly, barely noticed—the villagers no longer rely on the schedule of prayer to tell the time of day.

Coming from a much more frenetically paced world, Canato stumbles upon the slumbering village like a lost traveller. An unnerving quiet pervades the site. It seems like an unknown atrocity has emptied the place, some nuclear disaster like Chernobyl or Fukushima, but nothing so catastrophic has caused people to abandon these buildings. The anachronistic contents of the houses, neatly packed away, show the village simply as a casualty of the slow demise of a centuries-old way of life, still visible as ruins, and at its centre an ancient church. This place waits, undisturbed, as if for the fabled kiss that can bring life back to cold, dead lips.

Thea Costantino, Curtin University, 2013